How The NBA Explains The Entertainment Industry.

A tale of legacy, disruption, and who really makes the plays

I started this newsletter to be an open palette to consider the myriad issues facing my industry, and to work through potential solutions. Disruption and disruptors have always fascinated me, and now NonDē1 has taken root in my brain to the point that the majority of my conversations these days somehow lead back to the ways in which creator economy principles can cure just about all the ills that plague the entertainment industry. My wife can see it coming a mile away.

But it’s been the discussions with directors that have stuck with me the most. Whether it’s with clients or collaborators, chats with filmmakers about their place in our current moment of uncertainty and upheaval have been hard to shake. How are they adapting? What structures are in place to give them a chance to succeed in a NonDē environment?

Directors are the lifeblood of the film and television industry — the only ones with both the storytelling capacity and technical chops to make a film happen — and it feels necessary to put them at the center of the conversation about the future of the film business.

Filmmakers amaze me. I have worked with first-time directors, and ones with decades of experience, ones that also write, and ones that used to act. I have studied directors closely and from afar. I was also raised by one. From all these encounters, I often equate the role of the director to that of a basketball coach. Follow along with me:

While the action on the court is executed by players that are the unquestionable stars and the primary draw of the fans (actors), who were selected and are paid by the general manager and team owner (the producers and studio), and who run the plays generally drawn up by the lead assistant coaches (writers), the coach is the fulcrum of the entire operation. They are beholden to everyone and no one at the same time, empowered to make the most consequential decisions, but only with the resources given to them by management. They are the first person honored in victory, and blamed in defeat.

To borrow a construct from the great cartographer

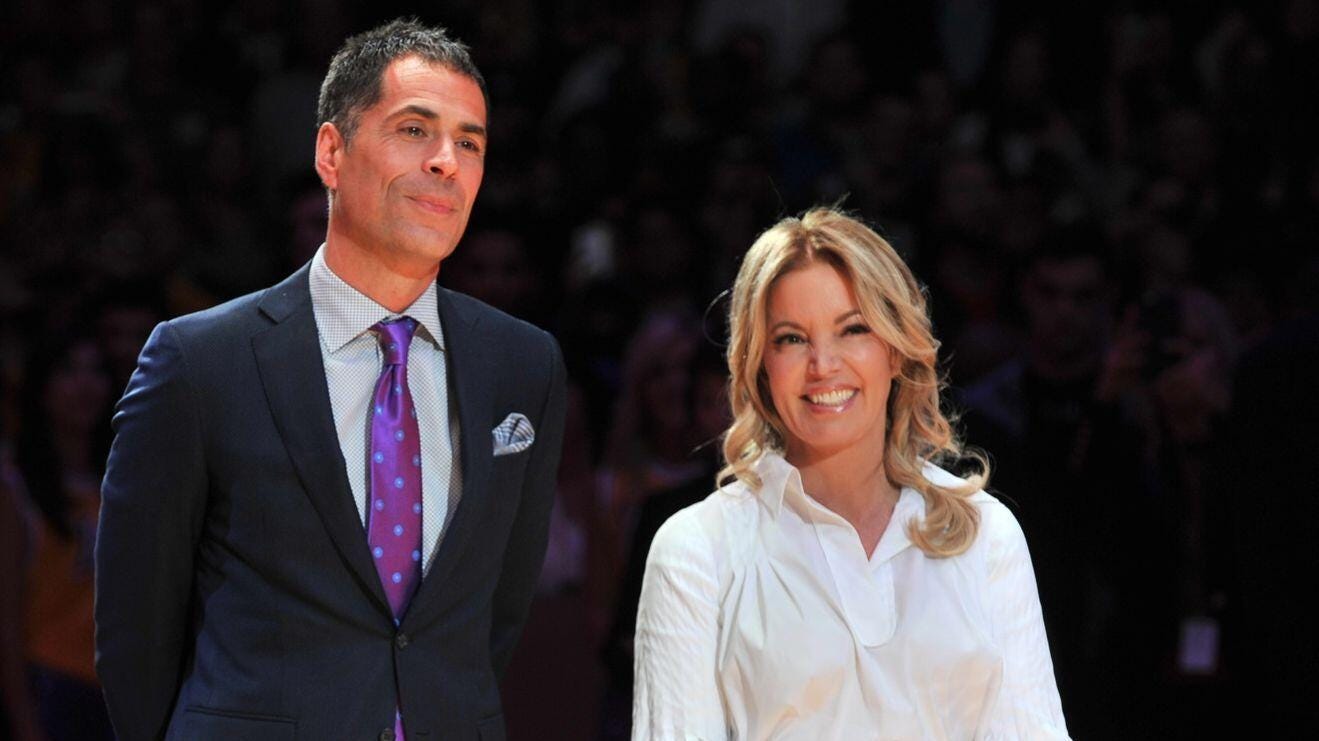

, I see the 2025 media landscape as a mirror of the NBA. There are big market legacy teams (WBD, Universal, Disney) and small market upstarts (Netflix, YouTube, Tubi, etc.), there are superstar players (Cruise, Pitt, The Rock, etc.), and disgruntled coaches (basically every director right now), all trying to win championships for overpaid executives increasingly looking to maximize shareholder return (Zazzzzzz) or sell to private equity (A24, Mubi).The heart of this league is the legacy media — a small handful of studios that built the league and thrived for 100 years. Today, the Legacy Media team is unequivocally broken. Sure, it was massively successful for decades, nearly without threat or competition. But then atrophy set in. Leadership was passed around among friends and family, none of whom had any particular aptitude for the sport or drive to innovate, let alone to put systems in place to ensure operational stability. Infighting among the owners was rampant, and a rotating cast of high profile executives promising to turn things around continually resulted in controversy. Coaches came and went regularly. Any success could easily be construed as a happy accident: a lucky draw in the draft, a single trade, or a major star deciding to play there based solely on tradition or proximity to ancillary sources of income.

In other words, legacy media is the Los Angeles Lakers.

BUT! Contrary to what ESPN may have you believe, the Lakers are not the only team in the NBA. The league in 2025 is a dynamic landscape full of challengers to the status quo. Five teams in particular have led this disruption: the Warriors, Clippers, Thunder, Spurs, and Heat. Over the past two-plus decades, this group of long-dormant organizations have implemented systems to set their coaches up for long term success by committing to novel approaches to organizational culture, team building, asset management, and investment in data and infrastructure. As a result, the Disruption Teams boast four of the six longest-tenured current coaches, and the fifth, Gregg Popovich, just retired after nearly three decades with the Spurs.

These organizations zigged and zagged, where the Lakers stayed put. Instead of relying on their brand equity from dynasties of bygone eras, convinced of their own superiority, these teams took inspiration from outside voices and industries, namely tech and private equity, to rethink how basketball could be played, how organizations could be run, and how a team’s brand could grow. They identified generational talent and allowed coaches to run plays that maximize those talents. And they infused cash to build out ancillary products and that attracted better players and more fans. And guess what? It worked. The Lakers may have as many championships as all those teams combined (17), but since 1999, the Lakers have 5 titles, while the other teams listed above have combined for 13 (the Clippers haven’t won any, but they do have the longest current streak of winning seasons2).

What does this show? That a century of nearly hegemonic success can be disrupted, but is very difficult to supplant completely. In our entertainment ecosystem, the obvious disruptors are Netflix and YouTube, with Apple/Amazon, and TikTok/Instagram (even Quibi!) not far behind. These folks acted differently because they had to in order to break in — to take down a dynasty, if you will. They introduced streaming video, full season television releases, algorithms, short form, vertical video, subscription models, etc. And it has worked! Film and television studios were so blown away by Netflix that they ALL tried and failed to build a rival streaming service (the Lakers, on the other hand, never even tried to find three point shooters).

Nevertheless, LeBron still came to LA and got the Lakers a Bubble Ring, and Warner Bros. still manages to avoid David Zaslav’s self-harm long often enough to land a couple blockbusters each year. No matter how many SpinCo’s get spun off, or mini-majors get merged, there’s always another Moana, Jurassic Park, or Despicable Me these studios can crank out, and somehow the Lakers still manage to land Luka Doncic (without even giving up Austin Reaves, Dalton Knecht, or more than one first round pick!). Success begets success, sometimes in spite of itself.

Ahh, but a glimmer of hope arrived two weeks ago: Mark Walter, CEO of Guggenheim Partners and owner of the LA Dodgers. Walter, the NonDē scion in our metaphor, just bought the Lakers for $10 billion — the highest amount ever paid for any American sports franchise. Since Walter took over the Dodgers — another storied franchise — in 2012, he has turned the organization into the crown jewel of pro baseball, sparing no expense at every level, from player salaries, to scouting personnel, to analytic technology. He even replaced the toilets in order to land a pitching phenom from Japan.

During his tenure as owner, the Dodgers have the most regular season wins in baseball, they have the longest active playoff streak, and they have won two World Series. It should come as no surprise, then, that Dodgers manager Dave Roberts has been the coach for 10 seasons, the second longest-tenured manager in baseball.

In other words, Mark Walter — the guy who transformed another tarnished legacy brand into a gleaming standard-bearer — is about to take over a broken machine that still, somehow, produces serviceable, if not occasionally exceptional, products. With the Dodgers, he did so by investing the right money in the right places (namely, in Shohei Ohtani), rethinking local broadcast rights deals to support an unrestricted salary structure (to afford the most expensive roster in baseball, including Ohtani), and by taking on previously unthinkable risk with deferred salary commitments for generational talents (Shohei, et al.). With the Lakers, he seems to have already started to look forward by focusing this offseason on the young superstar (Luka), rather than catering to the aging legend (LeBron).

Thinking differently, leveraging opportunities, identifying exceptional personnel, giving them the resources and latitude to take risks, investing in innovation, salvaging brand equity. Sounds like a damn good formula to resuscitate a team, or an entire industry. Think David Ellison has it in him?

I’m not so sure either. And for now, that’s not my concern. I’m keeping the focus on the micro-teams I work with — individual filmmakers, films, and production companies. My primary question is: How can I put the coach in the best position to lead the team to win? As a lawyer, what are the terms that will help a director succeed not just on one project, but in building their brand and audience connection, such that the next project is even easier to fund and execute? As a producer, who are the personnel that need to be above and below the line that give the director the most opportunities for success? In other words:

How do I help filmmakers shake the development-industrial-complex habits of the past, and step into the audience-and-economy-building system of the future?

And, perhaps most importantly, how do we bring a championship to the best team in Los Angeles — the Clippers.

If you don’t know, now you know.

And a very special place in my heart.

Shaka King, RaMell Ross, Yorgos Lanthimos, and Spike Lee would approve of the basketball coach to movie director analogy