Independent film studios are one of the last places in Hollywood where real budgets still get behind new voices. That may be about to change.

Mubi just raised $100 million from Sequoia Capital at a $1 billion valuation. It was a giant investment, at a time when the indie studio and niche streaming service is really starting to flex — it made the largest acquisition at Cannes this year, a $24m acquisition of Die My Loves starring Jennifer Lawrence and Robert Pattinson For a company known for curating international arthouse films, it’s a major leap, one that signals a broader trend: Private equity money is flooding into independent film, and with it comes a very different idea of what creative success looks like.

The Seduction of "Scalable" Art

With any private equity investment, growth is the destination. Money is invested based on a projected value of the company, and the investor plays a huge role in determining that value. In other words, the value is all in the investor’s eye (i.e. “Your company is worth X, but with my additional capital, I think your company can be worth Y.“).

The question for the observers then becomes whether the investor believes that (a) the company, as it exists, can scale simply with additional resources and operational support, or (b) the company has something good going, but necessarily has to adjust in order to achieve the projected value.

This red pill/blue pill dichotomy can be no more clearly summed up than in the quotes provided by both side of this Mubi deal. Mubi’s founder Efe Cakarel is sure that this investment will not alter the trajectory or values of the current arthouse darling:

“Just remember what brought you here. Take the long-term view. Don’t do anything short term for short-term gain. Don’t chase popularity or box office. Just get on a bike and ride.”

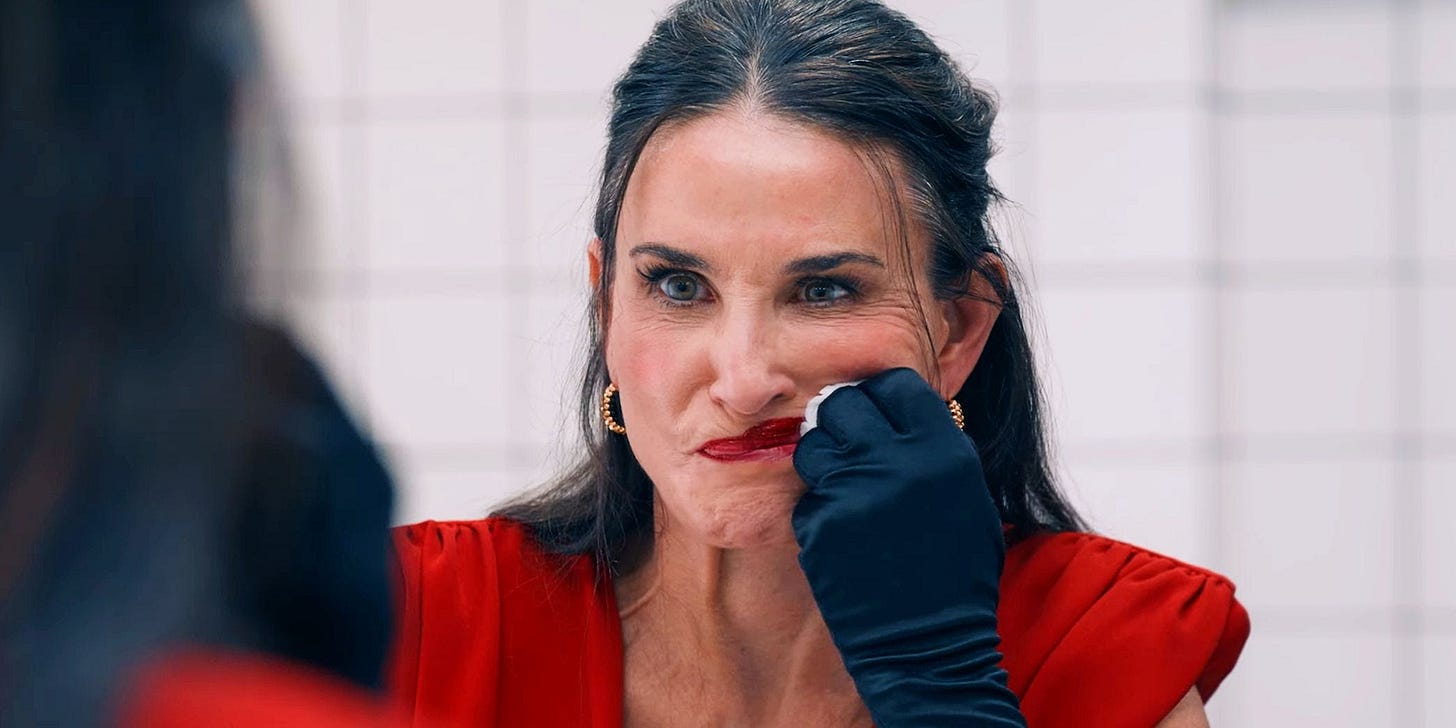

Mubi’s film acquisition strategy has been driven by quality and an attention to a very specific point of view, that has yielded incremental gains over a long period of time. When Cakarel described turning "a body-horror film from a director that no one ever heard of" (The Substance) into "a cultural global phenomenon," he was describing something that happened organically, through word of mouth and critical acclaim—not through algorithmic optimization.

But when Sequoia Capital's Andrew Reed explains their Mubi investment, he sounds a lot more like every other investor looking for a unicorn with global scalability:

"The question is, how many people around the world will projects like this resonate with? Our opinion is that this is going to resonate with a lot more people than anybody thinks."

What many private equity firms have found is that independent film has never been about scale. It's been about specificity, about telling stories that the market might not obviously demand, but that culture desperately needs. Will Mubi stay on that long term, diamond-in-the-rough path, or pivot to meet its new billion-dollar valuation?

The Cautionary Tales, and What Falls First

There are two PE-backed, independent studios that we can look to as cautionary tales for what happens when private equity meets independent film.

A24 spent a decade of steadily building its brand as the coolest label in film — full stop. From Oscar winners Everything Everywhere All At Once to Moonlight, and dozens more — thee studio had an absolutely insane run of movies that were wholly original, not very expensive, and effectively the opposite of what the other major studios were making. Audiences loved it, to the point that A24 became the first branded and consumer-recognized movie studio since….Disney?

And in 2022, it made the decision to take outside money, raising $225 million from Stripe at a $2.5 billion valuation—nearly doubling its worth overnight. And last year, they doubled down, taking on another $75m at a $3.5b valuation. These are enormous leaps in the company’s projected value, and they have brought a predictable pivot toward more commercial content and an expansion into new business such music representation and live events. According to Hollywood Reporter, A24 executives are now asking for "the A24 version" of commercial properties—wanting to know what their take on John Wick or Suits would look like. This represents a fundamental shift from finding singular visions and figuring out how to market them, to starting with market demand and working backward to creative decisions.

Around the same time A24 was founded, Media Rights Capital (MRC) burst onto the scene with boatloads of money and a gameplan to match: sell big projects to big distributors. Around 2011, they acquired the rights to a British political drama called House of Cards, and deficit financed the first two seasons of the Kevin Spacey-Beau Willimon-David Fincher political thriller before selling it to Netlfix. MRC has never positioned itself as a particularly “indie” or arthouse brand — it subsequently produced big-budget, commercial series and films Ozark, Terminal List and the Knives Out franchise — but in 2019 it saw enough value in attracting more storytellers to the company that it opened a non-fiction department to finance and produce prestige documentaries.

In both instances, first victim of the PE Pivot is documentaries. In 2023, MRC shut down its doc division despite having more than 10 projects in production, including two that would go on to open Sundance: The Greatest Night in Pop and Sly Lives! (aka the burden of Black genius). My own documentary, a series called Black Box, which MRC acquired in 2020, is currently sitting on their shelf, 75% through post-production, presumably because it doesn't fit their return-on-investment calculus.

And just two weeks ago, A24 shut down its documentary division entirely. Documentary filmmaking has historically been the most vulnerable, least profitable corner of independent cinema — but one that had a passionate following, and the relatively low budgets provided an opportunity to grow brand equity at much lower risk than a project with a 10x budget. But when you're valued at $3.5 billion and have PE investors expecting exponential returns, small-budget docs that might gross a few million at best become administrative distractions rather than cultural investments.

Mubi's Crossroads

Mubi finds itself in a uniquely interesting position. Unlike A24, which is primarily dependent on theatrical releases and streaming sales, Mubi has its own distribution channel through its SVOD service and an established indie brand. This gives them options that other studios don't have.

They could continue building their streaming brand as the ultimate destination for independent film voices—serving their niche audience consistently and profitably without needing massive box office returns or big-budget streaming deals. Their $1 billion valuation could support a sustainable business model focused on curating and producing quality independent content for their dedicated subscriber base, in tandem with the occasional global box office hit.

Or they could follow A24's path and pivot toward larger commercial projects, chasing the exponential growth that Sequoia Capital likely expects from their investment.

I hope it’s the former, because what A24 created, and what Mubi is building, is the lifeblood of a thriving creative ecosystem. The creative process that generates the breakthrough films like The Substance is inherently anti-scalable. It requires giving filmmakers creative freedom, taking risks on unproven concepts, and accepting that many projects will fail commercially even if they succeed artistically.

What Comes Next?

Either way, I am less concerned with whether A24 or Mubi will be successful in their next phase—I am sure they will return plenty for their investors. The most important question for me is whether the independent film industry will adapt by finding investment models that actually align with how creative businesses work, or whether we'll continue watching cultural institutions get optimized out of existence.

One model to consider: Micro-cap investors. Micro-cap private equity firms (ones that invest in companies valued from $50-$250 million) don't chase unicorns. Instead, they focus on smaller, steadier gains over the long term, deriving value from dependable, mostly inelastic businesses. Think HVAC companies, accounting firms, dental practices—businesses with predictable customer bases and steady cash flows that don't need to grow exponentially to be valuable.

The key insight from micro-cap PE is that you don't need to dominate markets—you need to serve them consistently, create efficiencies of scale, and slowly expand their customer base over time. A studio that made reliable, profitable faith-based films, solid genre content, or quality documentaries for specific audiences could generate steady returns without needing to chase the massive hits that small or large capital investors demands. For digital-first brands and creator communities that have built dedicated audiences over time, the right investment could build out those offerings to expanded markets, without abandoning the core message or creator-audience relationship.

This approach would allow studios to maintain the creative risk-taking that makes independent film valuable while building sustainable businesses. Instead of needing every film to be a breakout hit, you're building a portfolio that serves specific, loyal audiences over time. This model would also preserve the creative ecosystems that are currently being dismantled. Documentary divisions wouldn't get shuttered because they'd be evaluated against appropriate benchmarks rather than expected to compete with blockbusters for ROI.

The HVAC Model for Film

The micro-cap rollup approach could be applied to two specific film sectors:

Creator Channel Rollups: Versions of this are already happening at a blistering pace, such as Propagate’s recent acquisition of creator management firm Parker Management. The idea is to acquire a stake in established creator channels with identifiable audiences and real expansion plans. Rather than building from scratch, you'd be buying proven audience relationships and scaling them systematically.

Production Company Consolidation: Roll up smaller production companies—there are dozens making exceptional work in low- to mid-budget narrative film, documentary, and even in the commercial spaces—and combine them with the acquisition of a niche digital distribution platform. This creates vertical integration for independent films while establishing a real brand identity, similar to what Mubi has built.

For the investor class, this may not be the sexiest opportunity, but it would certainly align more closely with the kind of Warren Buffett-mantra of slow growth and commitment to dependable industries, i.e. entertainment. And for the creative community, I take heed in what Brian Newman of Sub-Genre recently posted about protecting the voice of independent film:

We need to think more like Mr. Leo and step back, look at the bigger picture and build for the long term. That means investing in slates, or entire studios, focused on new narratives, not just single projects. It means trusting artists – with much bigger investments – to help us shape these narratives. It means thinking much bigger, again.

If we don’t rethink the capital stack of indie film, we’ll lose the ecosystem that made A24 and Mubi possible in the first place. I’d love to hear your thoughts, leave a comment below.

Some interesting things to chew on in this one

On the money here Sam!