Light Jokes in Dark Times

Why Making Comedy At Scale Is Harder Than Ever

Despite the success of Happy Gilmore 2 and some great reviews of Liam Neeson’s Naked Gun reboot, the word is that comedy is teetering on the brink of demise. It makes sense — I mean, what is there to laugh at? The world is on fire! Things are pretty dark out there, as the country and the world are in an inescapable doom loop. The steady headlines of war, famine, climate crises, criminal controversies, economic uncertainty, fascism, gun violence, you name it! It’s hard to ignore, and sometimes feels impossible to imagine something funny.

Comedy is a big broad sector of entertainment that has always been part of the human experience, especially when things seem darkest — what Matt and Trey made last week is the perfect example. Comedy movies tend to be the big swing dopamine hits, while standup and improv shows are the lo-fi comedy community sanctuaries. What interests me is how comedy can still reach a big, broad audience on a regular basis the way it did when I was growing up and weeknights on the couch with my family were spent laughing together.

We all used to laugh at the same thing. And that thing was called a Sitcom. Where does that comedy come from today? How will it get made, and how many people can it reach?

When the Sitcom Ruled

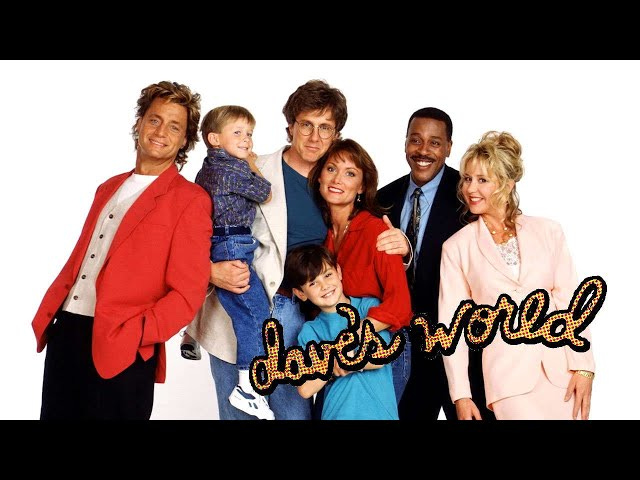

I grew up in the era of network television, where the 8-10 pm block on Monday, Wednesday, and Thursday night was primetime, where Friday night was TGIF, and Saturday was SNICK, then In Living Color, then SNL. It was the best. Comedy was all over television, the shows were great, and EVERYONE watched them. Even today, some of the most popular shows to stream are sitcoms from 20-30 years ago: Friends, Seinfeld, How I Met Your Mother, and The Big Bang Theory.

And from a network programming perspective, there were two genres of shows that ruled them all, two sources that brought in enormous amounts of ad revenue and offered a seeming limitless number of permutations to keep feeding the captive audience: Families and Workplaces.

If you are not familiar with these cultural staples, allow me to enlighten you. They were half-hour, multi-camera television shows, filmed in front of a live studio audience, and broken up by three ad breaks. The total runtime of the shows were 22 minutes, and the seasons were 20+ episodes long. And they were non-serialized, meaning every episode started in the same exceedingly ordinary living room or office, with a flawed lead character around which a cast of dependably sharp supporting characters could execute repeatable joke structures rooted in the lead character’s obvious foibles. You lived with these characters, and all of their mundane eccentricities.

In Family Sitcoms, they usually focused on the bumbling patriarch (Rosanne really broke the mold here), though some focused on a singular child actor (i.e. Michael J. Fox, Jaleel White, or Will Smith). But the formula mostly stuck to a head of household who, as an individual, was necessarily unremarkable. There was a spectrum of idiocy, of course — from Al Bundy to Ray Barone to “Toolman” Taylor and Dr. Cliff Huxtable — but across the board, the shortcomings of the dad were the central vehicle of the comedy, as Sharp-Tongued Wife + Defiant Child A/Stoic Child B/Wacky Child C + Goofy Uncle/Grandma/Neighbor rounded out the ensemble. Or they were aliens (see: 3rd Rock From The Sun).

Meanwhile, workplace comedies squeezed every last ounce of juice from the tree of the mundane. The only place besides homes that people went EVERY DAY was work, and it proved to be the perfect source of relatable comedy. Offices that were open to the public allowed for seemingly limitless material — bars (Cheers), city hall (Spin City), and tv or radio stations (Murphy Brown, News Radio, Frasier, WKRP).

And it worked. SO WELL. Despite serving only 3, then 4, primary programmers (UPN and the WB showed up in the mid-90s), studios developed and pumped these shows out by the dozen, and piloted hundreds more. This pilot system, expensive though it may have been, was a necessary filtering mechanism for trying on characters that networks hoped audiences would live with for years. You couldn’t greenlight those series on a pitch or a script alone, you had to see the rhythm, and feel the chemistry play out on screen first.

Daniel Parris crunched the numbers on a sitcom boom that provided thousands of long-term jobs to actors, writers, and crew members, bolstering an ecosystem that ran on a regular schedule every year: Pilot season every February-April, Sales season in May, Summer reruns, then Production season in the fall and winter. When the fall schedules came out, the Family and Office comedy subgenres were really the primetime workhorses, driving in dependable ad dollars between time slots of big swing projects that tended to highlight popular standups (Seinfed, Jeff Foxworthy) or more non-traditional families (Friends, Will & Grace, Mad About You). So why did these shows work so well — and why did they fade away?

TV Comedy as a Reflection of Society

Comedy relies on an underlying premise on which the audience agrees — a shared reality, a shared truth. And with sitcoms, primarily because of the repetition of scene and character, that underlying premise has to be nearly unassailable.

In the 1990s, that shared reality undeniably existed in the home and the office. The economy was booming, home ownership was high, everyone went in to an office or shop to work. The suburban single-income family with an Average Joe patriarch, a sharp stay-at-home mom, and two or three kids, was about as relatable as it got. The format was everywhere because the idea of an unremarkable person owning a house with the big yard, taking family vacations, and regularly splurging at the mall weren't aspirational plot points, they were just the backdrop against which the real stories played out. Similarly, workplace comedy could reasonably derive from a clumsy boss precisely because the viewer had a boss JUST like that, and his or her job security was solid as a rock, which made it easier for individual network executives to pick shows the would resonate with broad audiences.

But by the 2000’s, that shared reality began to crack, and sitcom production began to drop off. One undeniable reason: cost. The massive success of the sitcom had steadily increased the cost to produce them, and when a cheaper form of television called Reality TV hit the scene, it started eating up time slots.

But the world changed pretty drastically around that time too. September 11th hit, America went to war, and a few years later we faced the biggest recession in 100 years. Technology introduced things like the gig economy and content creators, and younger generations found it harder to get jobs, buy homes and start families. Just as income inequality was peaking, a global pandemic introduced remote work, and the political landscape went completely off the rails. In the process, the notion of a shared experience rooted in domestic prosperity and steady employment eroded. So no wonder network executives had a tough time picking tv shows about home or office life that resonated beyond niche demographics.

The Sitcom Comeback

Today, a show about a single income household supporting three kids in the suburbs could only mean one thing: trust fund baby or finance/tech executive making millions. That’s just not relatable, let alone funny. Twenty-four episodes with that family only works if you are skewering them (see: Succession, Arrested Development, and Silicon Valley).

And that’s what happened: Comedy got a shade darker. Rather than live studio audiences, single-camera shows have taken off, and with that, a slightly snarkier undertone that gave rise to more extremes ends of the character morality spectrum: from the deeply flawed series bordering on drama (from The Office and 30 Rock, to Curb, to Schitt’s Creek, Fleabag, Barry, Hacks, and The Bear, etc.) to the overly idealistic tending toward whimsical fairy tale (from Parks & Rec and Kimmy Schmidt, to The Good Place, Miss Maisel, and TED FREAKING LASSO). The family and workplace sitcoms have survived, albeit in smaller numbers, and also without the audible audience laughter (Modern Family, Black-ish, Abbot Elementary, Only Murders), while serialized comedies (Nobody Wants This, Dear White People) give audiences the dopa-rush of a singular, propulsive storyline.

Networks and streamers choose these shows because the cost is low, they lean into extremes (biting satire on one end, earnest uplift on the other), and they inspire active, loud engagement. This is the opposite of the traditional family or office sitcom, which allowed for a more passive viewing experience, with comedy that played toward the middle. So I think the future of this type of television depends on the reconsideration of that other factor: cost.

YouTube as the New Pilot System

The stories that will resonate most broadly will necessarily be different than those 20-30 years ago. Maybe they'll be about families navigating hybrid work schedules, or kids teaching their parents about digital culture, or finding humor in the creative ways modern families make it all work. Perhaps they will lead with more women as head of house, or instead of the classic nuclear family in their suburban home, we'll see more shows about extended families sharing spaces, or communities coming together to support each other. There may even be a new form of universality trying to emerge today — not family or work, but something else. Group chats? Side hustles? Engaging online! Could those be the new premises? The family or office sitcom may be evolving, but the desire to see our lives reflected back to us through the lens of humor remains constant.

And you know where they will come from? YouTube. The very nature of content creators is iteration and experimentation, sharing new ideas, and measuring the audience’s response. In the comedy world, that generally takes the form of sketches and standup, where comics can try bits and cut up specials to go viral. But I think there’s a place for scripted comedy development too, and an opportunity for traditional television financing entities to introduce a new pilot ecosystem by investing in the creators that are already looking for broad audiences with relatable humor.

The next NewsRadio or Everybody Loves Raymond won’t be picked from a pilot script or a pitch deck. They will be cultivated in partnership with a creator who developed characters that are actually reflective of the world in which that creator lives, and for whom audiences have already shown an affinity.

The bumbling patriarch may be retired, but the human need to see our stories told - and to laugh at ourselves along the way - isn't going anywhere. Even in the darkest times, we still need the light of a good joke.”

Love this Sam! As I’ve been diving into a more public phase of High Concept I’ve been thinking like a content creator on the marketing and distribution side— iterating and sharing as I start to bring our proof of concept projects to life and find our audience before we shoot.

As a filmmaker who always kept things precious waiting for that perfect pitch opportunity its been very gratifying; I’m only adding more depth to the world of my projects, really getting to know them and they seem to be more naturally progressing to next steps!

"Networks and streamers choose these shows because the cost is low, they lean into extremes (biting satire on one end, earnest uplift on the other), and they inspire active, loud engagement. This is the opposite of the traditional family or office sitcom, which allowed for a more passive viewing experience, with comedy that played toward the middle. So I think the future of this type of television depends on the reconsideration of that other factor.."

SO smart, Sam. And your answer about YouTube is equally adroit. And yeah, it's that good. I used the word "adroit," to describe it. I was just in a meeting discussing this very idea of YouTube. How it stacks up against Netflix in how it pays its successful creators.