Let's Talk About Paying Documentary Subjects

Why it's time for filmmakers to start disclosing whether doc subjects are being compensated

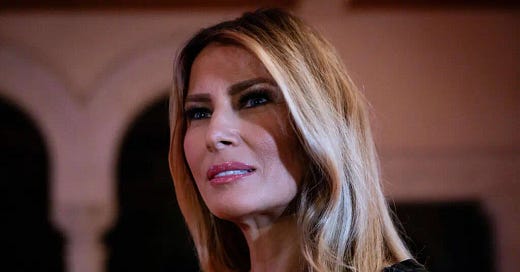

According to Puck, Jeff Bezos is paying $40 million to Melania Trump for a Brett Ratner-directed documentary about her life. Of all the gross things in that sentence, I want to talk about what is likely the least politically charged, but most consequential to the day-to-day life of the documentary film community: the practice of paying documentary subjects.

After decades of a broadly-held, hardline ethical stance against compensation of any sort to documentary subjects, the documentary world has loosened its position over the past decade. For myriad reasons, including the rise in IP-driven film development, where a producer secures the exclusive rights to a book, article, or person’s publicity rights in exchange for a fee, the relationship between filmmaker and subject has blurred significantly. Whether they are hidden in materials or access fees, presented in the opening titles with production company or EP credits, or slipped in via backend points, the benefits received by a documentary subject can vary, as can their influence on the final film. Executives, producers and filmmakers will publicly decry the practice and profess outright objections to “paying documentary subject”, but the reality is this is nearly ubiquitous — many subjects are getting some form of benefit in addition to the exposure of the documentary film.

This hypocrisy — or rather, obfuscation of reality — has left the industry lost in a sea of ethical, financial, legal, and producorial uncertainty, with filmmakers often pinned into the impossible position of trying to determine whether offering a benefit to a subject — be it a nonprofit organization, a researcher that also appears on camera, a war refugee, or just an Average Joe whose is taking time away from their day job to participate in this film — is ok.

1. What is allowed, and what is not allowed?

Here’s what I know from my decade in documentaries as both a producer and attorney: compensating subjects either financially or with a credit is unquestionably “allowed”. But the degree to which, and the circumstances in which it is allowed, appear to be utterly unknown, undecided, and up for debate.

I have been the lead producer on two streaming commissioned projects: Blackballed (2020, Quibi/Roku) and As We Speak: Rap Music on Trial (2024, Paramount+), both of which engaged on-camera subjects to some degree. On Blackballed, a doc series about race and the NBA, Doc Rivers, Chris Paul, and DeAndre Jordan served as executive producers. They were not paid, nor were they given any editorial access or control. Their credits were requested and gladly given because they provided the service of reaching out to other potential subjects to appear in the film — from basketball players JJ Redick and Matt Barnes, to Disney CEO Bob Iger, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver, and former LA Mayor Eric Garcetti. They provided their relationships to benefit the project, and what they received was an EP credit in return. It all felt like a just outcome.

In advance of the release, we reached out to media outlets for advance press screenings and reviews. Uniquely, The Ringer refused to review the film explicitly because of the EP credits provided to the subjects, stating that the project was clearly a vanity project of the athletes telling their own stories. Of course, this couldn’t have been further from the case, but it was a somewhat reasonable reaction, given the fact that other athletes, who had taken similar credits, were in fact making vanity documentaries with total creative control (interestingly, The Ringer had no objection covering The Last Dance).

So in this instance, the filmmaker offered the credits and studio/distributor allowed the credits, but the media said that a documentary subject with an EP credit is not allowed…in this instance.

2. How many people are paying subjects?

Who knows! Clearly Melania (and by extension, her husband) is getting paid. I’ve heard that Billie Eilish benefitted from Apple’s $20 million acquisition of the documentary about her, The World’s a Little Blurry, David Beckham for the doc series about his life, Beckham, and Michael Jordan for The Last Dance, but I cannot confirm any of that. LeBron James has served as subject and production company on a handful of doc projects and series, for which he or his company, Spring Hill, is undoubtedly compensated as well. And it has been reported that Beyoncé has a deal with Netflix that includes documentary projects about her. But I am not sure who else is getting paid — was the estate of Christopher Reeve compensated for Super/Man, or the estate of Jim Henson for Idea Man? Was Martha Stewart compensated for Martha, Michael J. Fox for Still, Selena Gomez, Pamela Anderson, Lady Gaga, or Michelle Obama compensated for their docs? I do not know, but I have my suspicions.

The point is, it’s likely quite prevalent, if not necessary, to pay subjects — especially high profile celebrities — to make a documentary. Without payment, engagement from a high profile subject could be stifled. Case in point: In 2024, my documentary As We Speak premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, then screened at DocNYC Selects, and was released on Paramount+ a month later. One interview subject, professor Erik Nielson, who had co-authored a book about the subject matter of the film and helped facilitate most of the expert interviews in the film, was credited as a Consulting Producer, for which he received a fee in the network-approved budget.

One prominent artist that we approached for an interview requested a $25,000 fee, which was denied. The most high profile artist that did appear in the film, rapper Killer Mike, was not credited or paid, and providing either of those things was never an offered or supported by the commissioning streamer, Paramount+. Mike generously provided two hours of his time for an interview that was the first and one of the most impactful conversations of the whole film. However, without the extra buy-in from the studio, his commitment was limited to that single appearance, and he did not participate in marketing the film at festivals. This was completely justified on his end, as his appearance was not contingent on payment or a credit, and the festival appearances would have only been to benefit the streamer. Plus — every other streamer is doing it! Nevertheless, the film and filmmaker were unable to benefit from Mike’s otherwise interest in and support of the film. (He did graciously post about the film on social media, and he has been a staunch supporter of the cause the film discusses for more than a decade. RTJ forever!)

3. What’s the solution?

In order to find a solution, we have to agree there is a problem, which in my eyes, are two: (1) debilitating confusion for filmmakers in what is allowed; and (2) confusion for audiences about the conflicted interests in purported works of nonfiction. I’m not best suited to analyze the latter, but I know the former anxiously wrestles with this issue, which has the effect of stifling work.

I represent documentary filmmakers in all stages of production, and where I find I am needed most is during development and early production — when doc filmmakers are forming relationships and negotiating appearances with potential subjects. This is the most precarious phase of the filmmaking process, where guidance is needed most, and where I try to lead them toward the most ethical, legally defensible, and commercially beneficial solution. But what is the right answer in these scenarios:

A film is about work being performed by individuals tied to a nonprofit. Can the nonprofit receive backend points?

A projects starts with the life rights to two individuals that went on a great adventure. But in order to complete the doc, you need to travel and shoot at least 24 more days with the individuals, who have day jobs, families, and little time off. Can you pay them a fee?

A person is approached to be in a doc about an organization they were involved with years ago, and have distanced themselves from. The person does not want to appear, but they have a trove of documents related to the organization. Can they receive an appearance fee? A materials fee? Can they be credited as an EP, especially if they allow the producers to attract other subjects?

I can tell you that drawing a consistent conclusion from the way that each of these scenarios played out would be impossible. Filmmakers, studios, producers, financiers, streamers, may all fall on different sides.

So the bigger question is: WHO is the arbiter of right and wrong here?

If sunlight is the greatest disinfectant, then let’s let the sun shine!

At the end of the day, films are made to be seen, and documentary films have a unique relationship with audiences: they are to be seen as presenting information — with a point of view.

Audiences need to know what that point of view is:

Is it strictly the POV of the filmmaker, or is it the POV of the main subject, with the input of the filmmaker?

Is it the POV of the filmmaker, with consultation from the subject, or is it the POV of the filmmaker, with final say by the subject?

Or is it the POV of the subject, who is getting paid $40 million by owner of the streamer in order to curry favor with the president of the United States?

All reasonable questions to ask!

And I think this movement can be led by those with no financial or credit obligations to subjects. If your film is entirely divorced from any involvement by on-camera talent, why not include a chyron before the end credits declaring the same?

This film was developed, produced, and distributed without input from or financial benefit to any on-camera subject.

And if one subject served as a consulting producer or EP because they actually helped get it made, why not disclose that? I think it could have a great impact on the audience in understanding what they just saw, and it might call attention to those films that omit such a declaration. At the very least, disclosure would finally start an honest, open conversation about a widespread — but not inherently unethical — practice: paying documentary subjects.